Adele: my favourite musicians

Adele’s third album! This thing has become almost mythical in our culture, likeSalinger’s unpublished story trove, or the long-lost method of Incan stone-fitting. There were rumours that Adele would release 25 in 2013, the year she actually turned 25. Then the pop star herself hinted that the record would come out in 2014 – as indeed it might have done; a version was more or less ready to go last year, only for Adele to junk half the tracks. “I would have been embarrassed if I’d got away with that record. I was trying to hurry.”

Today, now, it’s ready. At supper time tonight, Adele will submit to her label bosses a final tracklist. First thing tomorrow, liner notes and promotional literature will begin to churn from print presses. Great pillars of CDs will start to cook in factories. Digital editions of 25 will be made iTunes- and Amazon-ready. Ads will be broadcast. And after that – who knows?

The last time Adele put out an album, her second, 2011’s 21, it returned seven Grammys, two Brits, two Ivor Novellos, three AMAs, two Aims, an Ascap, an Impala, a Mobo, two Music Week awards, two Q awards, four MTV awards, two Nickelodeon awards, a Glamour award, two German Echos, two French NRJs, a Polish Fryderyk, a Mexican Premios Oye! and a Canadian Juno. Sales-wise, it wasa generational one-off, a moon landing. As recently as August, 21 was still being bought a couple of thousand times a week. Estimated sales to date: 30m.

“But, no, see, this is the thing,” Adele says. “You can’t make assumptions. This new one could sell 100,000.”

It could. Though you expect some sort of nuke or pandemic would have to wipe out most of the waiting public first.

“Well, I don’t want to get my hopes up,” says Adele.

She waggles a sparkly boot. “I’m not arrogant. I’m not gullible. Some people I’ve spoken to have said, ‘You’re going to sell at least half what you sold before.’ But I don’t think anything’s a given. You don’t know.”

When I first met Adele, five years ago, we didn’t know. It wasFebruary 2011 and the musician, then 22 and very hectic, very gobby, had been flown to New York for a series of gigs and interviews. I followed her around for a weekend, hanging out with her small entourage while they shouted at each other in dressing rooms, gossiped, watched illegal streams of Premier League football matches, and impressed Americans wherever they went with their ability to cram swearwords into unusual crannies of speech. At the time I thought I was writing a story about a promising Londoner (born north London, raised south London, trained at the Brit School, signed to XL in 2006, her debut 19 out in 2008) who was trying to break America with her second album. Pop history suggested the effort would likely fail. But the attitude in Adele’s camp seemed to be: might as bloody well give it a shitting go.

“But, no, see, this is the thing,” Adele says. “You can’t make assumptions. This new one could sell 100,000.”

It could. Though you expect some sort of nuke or pandemic would have to wipe out most of the waiting public first.

“Well, I don’t want to get my hopes up,” says Adele.

She waggles a sparkly boot. “I’m not arrogant. I’m not gullible. Some people I’ve spoken to have said, ‘You’re going to sell at least half what you sold before.’ But I don’t think anything’s a given. You don’t know.”

When I first met Adele, five years ago, we didn’t know. It wasFebruary 2011 and the musician, then 22 and very hectic, very gobby, had been flown to New York for a series of gigs and interviews. I followed her around for a weekend, hanging out with her small entourage while they shouted at each other in dressing rooms, gossiped, watched illegal streams of Premier League football matches, and impressed Americans wherever they went with their ability to cram swearwords into unusual crannies of speech. At the time I thought I was writing a story about a promising Londoner (born north London, raised south London, trained at the Brit School, signed to XL in 2006, her debut 19 out in 2008) who was trying to break America with her second album. Pop history suggested the effort would likely fail. But the attitude in Adele’s camp seemed to be: might as bloody well give it a shitting go.

“That was mad, that weekend,” Adele recalls. “That was the beginning. That was mad.”

Before flying out to New York, Adele had sung at the 2011 Brit awards in London. Her rendition of Someone Like You, a ballad off the new album, had gone down well. Ovation on the night. Champagne sent to her table… Hungover, Adele climbed on to a plane to JFK and by the time she landed everything had changed. Her live recording of Someone Like You was fast bundling up the UK singles charts. (I remember Adele being put out: Someone Like You wasn’t supposed to be formally released as a single for months, so her diary was all out of whack.) When word came through that the song had gone to No 1, she went off for a pedicure.

Adele remembers it as a time of surprise and satisfaction; also of mounting terror. “I was frightened. I knew something was happening. Not to the level it ended up being. But I could feel this buzz. Suddenly there was the prospect of breaking America and it was, like, ‘Fuck.’” She says she felt oddly dislocated at the time. “Almost like an out-of-body experience. I remember my mum asking, ‘What’s wrong? What’s wrong?’” Adele couldn’t explain. “I could just feel something coming.”

Before flying out to New York, Adele had sung at the 2011 Brit awards in London. Her rendition of Someone Like You, a ballad off the new album, had gone down well. Ovation on the night. Champagne sent to her table… Hungover, Adele climbed on to a plane to JFK and by the time she landed everything had changed. Her live recording of Someone Like You was fast bundling up the UK singles charts. (I remember Adele being put out: Someone Like You wasn’t supposed to be formally released as a single for months, so her diary was all out of whack.) When word came through that the song had gone to No 1, she went off for a pedicure.

Adele remembers it as a time of surprise and satisfaction; also of mounting terror. “I was frightened. I knew something was happening. Not to the level it ended up being. But I could feel this buzz. Suddenly there was the prospect of breaking America and it was, like, ‘Fuck.’” She says she felt oddly dislocated at the time. “Almost like an out-of-body experience. I remember my mum asking, ‘What’s wrong? What’s wrong?’” Adele couldn’t explain. “I could just feel something coming.”

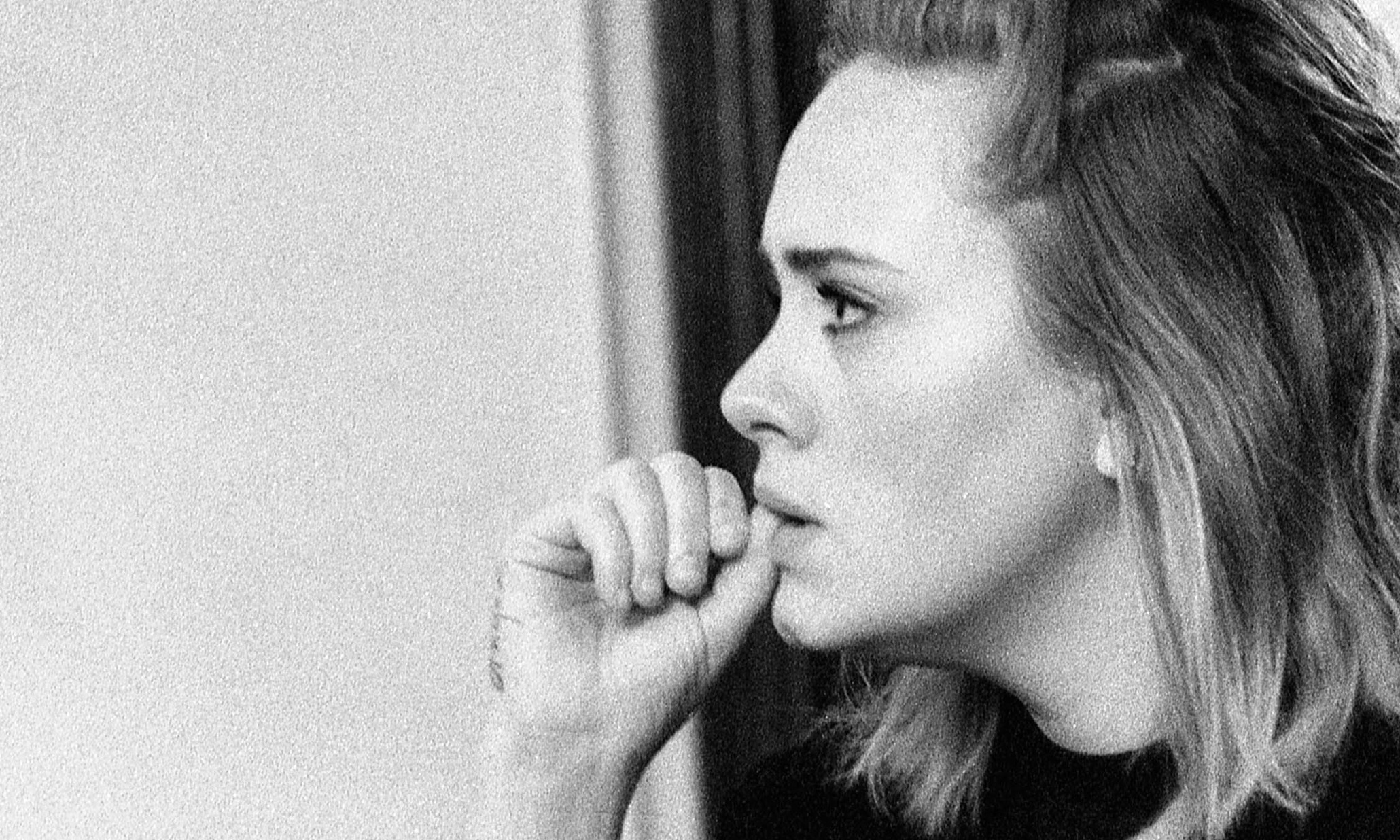

Adele at the Church Studios, London, July 2015. “I don’t want to get my hopes up,” she says about the expectation riding on her third album, 25. Photograph: Alexandra Waespi

Before long, 21 had gone to No 1 in nearly 30 countries. In the UK and the US it bedded in at the top of the charts for a month, for two – for half a year. Soon Amazon confirmed it had never shipped more CDs. Guinness kept preparing new bouquets of world records. Having already celebrated 21 as its album of the year for 2011, the trade magazine Billboard was obliged to make 21 its album of the year again, for 2012. The producers of James Bond invited Adele to sing the theme for a new instalment, Skyfall, and when it was released as a single, that sold millions, too. She won a Golden Globe. An Oscar.

In Britain, she became Miss Adele Adkins MBE, the honour lengthening her name even as Adele became so well known around the world that a first name would always do. When critics at Rolling Stone decided 21 was among the best albums ever made by a woman, Adele was pipped only by Patti, Stevie, Dusty, Joni and Aretha. When the Recording Industry Association of America upgraded 21 from “platinum” to “diamond”, Adele became one of few women to have achieved the loftier sales rank, along with Madonna, Mariah, Alanis, Britney and Whitney.

Her music was the most-requested in karaoke bars, the most played at funerals, “the best for nervous flyers”, “the most popular to fall asleep to”. It was said that, when a song by Adele played on the radio at Leeds General hospital, a girl awoke from a coma.

Reports about how much XL Recordings has earned from Adele have not always aligned, except inasmuch as everyone agrees it’s loads. The label still occupies the same tumbledown office it always did, on a mews in west London. Body-rubbed posters of affiliated artists overlap on the walls of the lobby, the one advertising 21 gummed up behind an umbrella stand. A fruit bowl has three shrivelled pears in it. On the reception desk there’s a flimsy boxfile with “Accounts and expenses!!!” felt-tipped on the front. Music Week guessed this company made a profit of £40m within a year of 21’s release.

Adele seems to have followed XL’s lead when it comes to downplaying financials. Though reports put her fortune somewhere north of £50m, she prefers to state the case this way: “I started shopping at Waitrose.”

Other things changed in her life. Definitely there were fewer queues, cruddy tasks, trips by public transport. At the same time she lost her access to some of the easy small talk and anonymity of everyday life. “When I walk into a room full of people that I don’t know, they stop talking. And I understand that. I get it. Because I’ve done it myself in the past. It’s just... If I go up to someone and ask what they do for a living, they’ll say, ‘Oh, that’s not very interesting, compared to what you do.’ But it is interesting. I’m interested. It’s real life, and I want to chat about it. Let’s chat about it today and let’s chat about it again tomorrow.”

It’s generally forgotten about Adele, in these days of her ubiquity, that she used to be cool. Cooler-than-you cool, a fringed teenager who went around behind aviators and Marlboro smoke, whose friends were mostly striving artists, who kept in her bag a copy of Time Out folded to the gigs page. When I first saw Adele perform, at a small London show back in 2007, she came on stage wearing a floral frock and a snarl. She played an acoustic guitar while drinking a pint. By the time I met her in New York, this phase was more or less over, the singer now dressing in black, favouring big lashes and lots of liquid eyeliner. The inner hipster hung around, though; Adele retains the use of a fully-functioning dickhead radar.

“What have I said no to? Everything you can imagine. Literally every-fucking-thing. Books, clothes, food ranges, drink ranges, fitness ranges... That’s probably the funniest. They wanted me to be the face of a car. Toys. Apps. Candles. It’s, like, I don’t want to endorse a line of nail varnishes, but thanks for asking. A million pounds to sing at your birthday party? I’d rather do it for free if I’m doing it, cheers...” At a certain point, Adele says, “money is all that gets thrown at you”.

Not that she hasn’t had her wobbles – succumbing to perks, lackeys, after-yous. “It’s very easy to give in to being famous. Because it’s charming. It’s powerful. It draws you in. Really, it’s harder work resisting it. But after a while I just refused to accept a life that was not real.”

What seemed unreal about it?

“Like.” She thinks. “Like, becoming OK with having things done for you. Or – no – expecting things to be done for you. I’ve had a few moments like that. And it frightened me. I think it was something simple like running out of clean clothes. And me not having the initiative to wash my own clothes. I was annoyed that my clothes weren’t clean.”

When was this? “Peak-y. Around the time of 21, when I was on top of the mountain.”

So? “So I told myself I’d better abseil down. And go and do my fucking laundry.”

Fame is charming. It’s powerful. It draws you in. But I refused to accept a life that was not real.

Occasionally, on the tracks I hear from her new album, Adele sounds as if she pines for her pre-21 days. “I miss my friends... I miss it when life was a party to be thrown...”

She says this isn’t the case, that she doesn’t feel any regret about the way things have gone. “I think everyone assumes I don’t like where I am, or what I’ve done, or what I’ve become. But actually I love it. Because I’m an artist, I have an ego, and it likes to be fed.” I sense Adele’s wary of being seen as that musician – the one who gets famous by singing about matters human and relatable, then afterwards writes exclusively about how awful it is to hop between five-star hotels on tour. “I was never going to write my record about Being Someone Really Famous. Because who cares?”

Still. One particular lyric, from a song called Million Years Ago, seems to point to an explicit malaise. “Around the streets where I grew up,” Adele sings, “They can’t look me in the eye/ It’s like they’re scared of me/ I try to think of things to say/ Like a joke or a memory/ But they don’t recognise me/ In the light of day...” This sounds like someone, I say, who’s stepped into a lot of rooms that fall silent. What does that feel like?

“It’s lonely. It makes you lonely. I mean, I can usually break the ice. If after 10 minutes people still aren’t saying anything, I’ll crack a joke, and I’ll go in to my scared-nervous-chat mode, like I do on stage, and make everyone laugh. But then I feel as if I’m performing. And I don’t know if that’s… Like… Don’t they ever want to meet just me? But then, at the same time I think, they’re probably not even there to meet me... I can’t explain.”

Try.

“Like, maybe me and my friends are going out to celebrate someone’s engagement. Or their birthday. Or we’re there to wet a baby’s head. It’s their event – it’s not about anyone meeting me. But that’s what it becomes. So sometimes it’s easier not to go.”

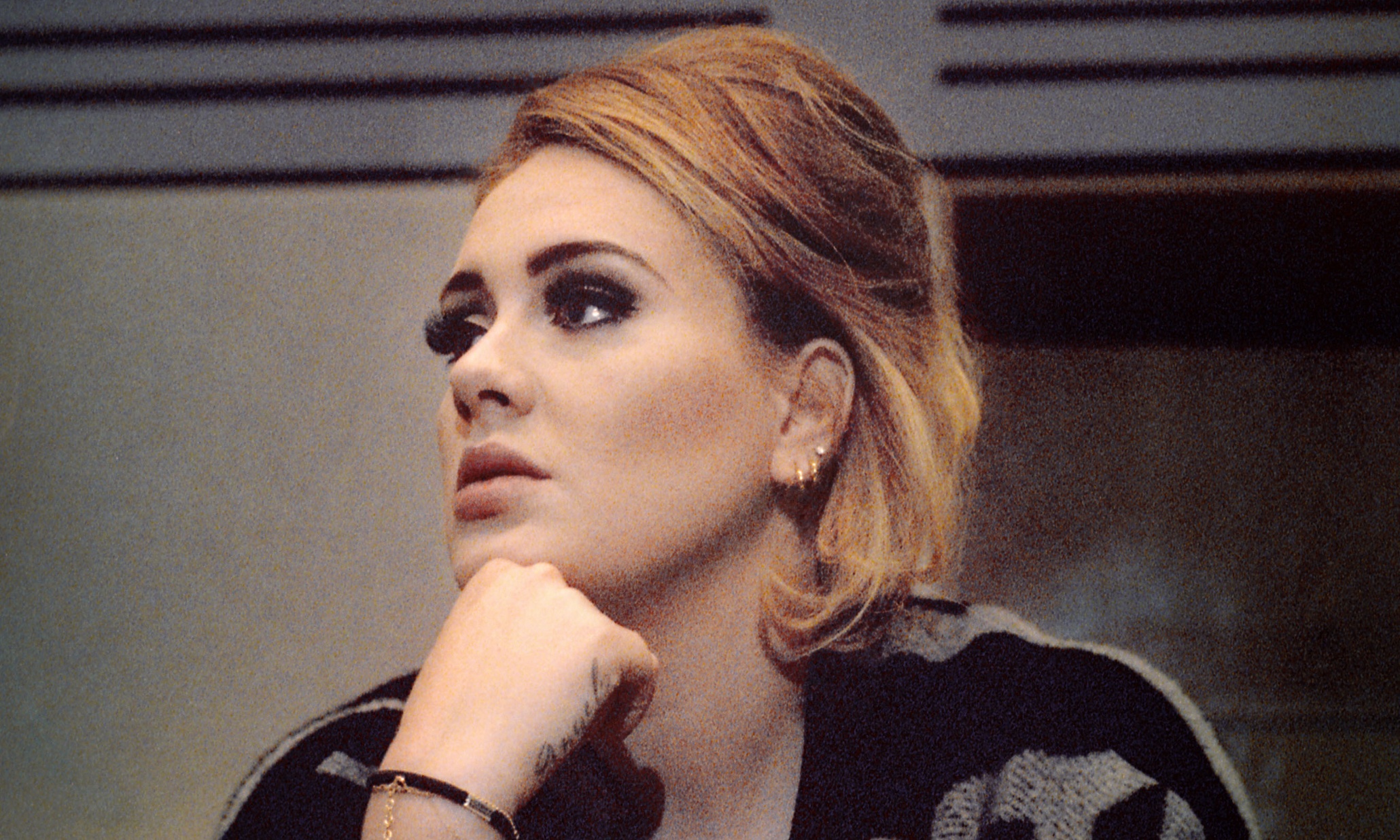

Adele at British Grove Studios, London, July 2015. Photograph: Alexandra Waespi

A contradiction troubles the very famous. Their renown makes them magnetic (“Look! Shh!”) and at the same time it creates real or imagined distance. They might only be exposed to the worst of the rest of us, inquisitiveness through a long-lens, clamminess up close. A personal example. Last spring I happened to bump in to Adele at a gig, the first time I’d seen her since our meeting in New York, and since the tropical storm of 21’s success. Ridiculously, surprisingly, I was starstruck almost to incoherence on meeting Adele – managing only a croaky greeting before scurrying away across the venue. Where, inevitably, I spent most of the gig craning my neck to gawp at her.

When I explain this, Adele smiles. A tell-me-about-it smile.

“In some ways I think it’s everyone else that changes,” she says. “Even more so than the person who becomes famous.”

Afew years ago Adele settled down with a new boyfriend, a charity executive called Simon Konecki. In 2012 they had a son together, Angelo. Gawping from a distance, it appeared as if romance and motherhood provoked a period of hibernation. Reclusiveness, even.

“I’m not a recluse,” she says. “Can we clear that up? I didn’t stop going to shops. To parks. To museums. I just wasn’t photographed while doing it.”

We saw her out at two Brit awards, two Grammys ceremonies, and in early 2013 she flew to Hollywood for the Globes and the Oscars, not so long after giving birth. (“Running to the toilet, between awards, to pump-and-dump. Which loads of people were doing, by the way. All these Hollywood superstars, lined up and breastfeeding in the ladies. No, I can’t say who. Because I saw their tits.”) After that, there wasn’t much to report. Tussauds unveiled a waxwork. When Adele wrote on Twitter, late in 2013, that she’d passed her driving test, it was as much as we’d learned about her in a year.

This isn’t common, a musician going dark at a time of high commercial appeal, and it seemed to baffle and even annoy people in her industry. “She’s a slippery little fish, is Adele,” complained Phil Collins, who’d been trying to get in touch about a possible collaboration. “I got through to someone, not her,” said Bob Geldof, when he was trying to book acts for Band Aid 30. “She’s not doing anything at all at the moment.” Adele: “I know some people thought I was mad for taking a break. Even I can see it was a bit weird. But I’m glad it happened. I think it was the right thing. It slowed everything down.”

What was the motivation to come back?

People found comfort in 21, because everyone can understand being disappointed by love

“Um. My son.” She explains. “I felt so mega having given birth; the confidence from that, I felt unstoppable. I’m sure most women feel that... Towards the end of the 21 stuff, I couldn’t remember why I was doing it any more. I couldn’t answer the question: ‘Why am I halfway around the world? On my own?’ But then, after I had my son, I thought, ‘Yeah, that’s why I did it all.’ I felt proud of what I’d achieved with 21 for the first time. And now everything I do, in every channel of my life, is part of a legacy that I’m making for my child. For my children, if I have more. I’m not motivated by much, certainly not by money – but I’m motivated by that. I want my child to see his mum running a proper business again. Being a boss again. Hopefully smashing it again.”

In the lounge at XL, we start to nod our heads, bounce knees, tap hands on available surfaces. Adele is playing a track called Send My Love (to Your New Lover), all beat and belligerence, the kind of pointy revenge song (think I Will Survive or Beyonce’s Irreplaceable) that makes you want to go out and find an unfaithful bloke, just to be able to toss him out and sing this stuff at him down the driveway.

“Send my love to your new love-HUH-er/ Treat her better.”

Watch Adele’s performance of Someone Like You at the 2011 Brit Awards.

Adele says, “This is my fuck-you song.” It was written in reference to the last guy, that never-named ex who dumped her when she was young, inspiring the best and saddest songs on 21. “It sounds obvious, but I think you only learn to love again when you fall in love again,” she says. “I’m in that place. My love is deep and true with my man, and that puts me in a position where I can finally reach out a hand to the ex. Let him know I’m over it.”

“My man”, by the way, is Adele’s go-to term for Konecki; much as “my son” is the only way she’ll ever refer to Angelo. A policy of namelessness seems to be part of a deal Adele has made with herself, a way of discussing her new album without too badly waiving the privacy of those closest to her. It must have been easier to cluck away about a meanie former boyfriend. He’d scarpered anyway! Adele has to be more cautious now. Her relationship with Konecki was first reported three years ago, when the pair holidayed in the Everglades and were surrounded by crocs, both real and carrying cameras. Every so often, since then, Adele has had to deny drippy tabloid reports that they’ve secretly married, or secretly split.

She sighs. They are still together. “Contrary to reports. Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes. And very happy.”

She plays another track, one called I Miss You, which Adele says she began to write one night while lying in bed, unable to sleep. “I miss you/ I miss you/ I miss you/ I miss you.” I ask her what Konecki makes of the song. “My man is loyal,” says Adele. “My man is strong. So we spoke early on, and he said, ‘Your writing isn’t anything to do with me.’ He’s fine with it. And it takes a strong man, I think, to be like that.”

I'm not a recluse. Can we clear that up? I didn't stop going to shops. To parks. To museums.

She wrote most of 21 during a series of one-on-one sessions with trusted co-writers. Same again with 25 – Adele plonking down near a piano with a super-producer such as Max Martin or Greg Kurstin, or maybe with a relative unknown (she found one collaborator, Tobias Jesso Jr, online), and seeing what emerges after a few days. This process proved fluid on 21. “That record was an anomaly – effortless!” Not so 25. Around the time of the Oscars, and up early that day with her kid, Adele spent a morning in the Hollywood studio of Paul Epworth, with whom she’d collaborated on 21.

“We fucked around for a bit, like an hour. And it became very clear very quickly that I wasn’t in the right headspace.” But she did pull together some songs, here and there, over the following year – eventually throwing away most of them, last autumn, on the advice of the producer Rick Rubin. He’s a friend, and flew to London to offer Adele advice on what she’d recorded. In a playback room much like the one at XL, Rubin was blunt: no good. “Honestly,” says Adele, “I was waiting for someone to say it.” What happened next? “I went back to the drawing board. Worked my arse off.”

Adele performing on Later… With Jools Holland in June 2007. Photograph: Andre Csillag/Rex

Adele thinks that part of the reason composition came so much harder this time was that she couldn’t completely lose herself, as she had before, in gutted-ness. “I couldn’t give in to any of that in order to access my creativity. There was no opportunity.”

Why not? “Because now I’m responsible for someone.”

It’s tricky to know how much to press Adele on Angelo. He is constantly, if obliquely, referenced in her chat. She has his name tattooed on the outside edge of her hand. The three-year-old even makes a charming bid for inclusion in our interview, when Adele speaks to him on the phone and has to tell him: “No, you can’t talk to the man. No, I can’t take a picture of the man.”

All the same, there are grimly necessary precautions that famous parents have to take around their kids. Recently, Adele won a legal action against a picture agency, Corbis, that had been involved in papping Angelo’s first trip to playgroup.

As a rule, Adele is inclined to share. At one point in our conversation, dissatisfied with her descriptions of a new tattoo of a dove on her back, she yanks down jumper and bra strap to reveal it. But circumstances have forced her to check what comes naturally, and when she discusses Angelo, today, the expression on her face betrays an obvious battle. Enjoyment of a sweeping and expansive gossip, on the one hand, and legitimate concern for her son’s privacy on the other. It’s a contradiction Adele sums up with perfect Adele-ness, when she shows me her Angelo tattoo and says, “What a cunt, right? I won’t say his name out loud. And then I go get it written on my hand.”

When the playback ends, and when Adele has dashed from the room for an exhausted wee (“Gotta piss!”), I ask her if we can go back and hear one particular track again. It’s a song called When We Were Young – and it’s in me, already, demanding a repeat listen.

“You look like a movie/ You sound like a song/ My god this reminds me/ Of when we were young.”

The song has an irresistible ambiguity to it, mournful as well as hopeful, exactly the combo that made Someone Like You so special. When she played the track the first time, she seemed especially anxious about it, reaching to make minute adjustments to the volume, then planting her fingers in her mouth to massacre the glue-on acrylics. Second time around, she keeps her eyes shut, nodding gently.

This is the one, then – the Hit Expectant. I can’t help thinking Adele has smashed it, as she’d hoped. The song just has that feel – a standard in the making, only waiting to become a part of the fabric of the coming years, chosen again and again on karaoke machines, picked out for people to get married to and buried to, centrepiece of an album that seems sure (however much she flaps her hand and demurs) to rattle the world the way 21 did.

Adele doesn’t know it yet, but when Hello, her first single from 25, goes on sale not long after we meet, it will sell half a million copies over two weeks in the UK, and 1.8m in the US. It will bundle up the charts to No 1 in both those countries, and around the world. Someone will train a speedgun on Twitter, and work out that 25 messages are being generated about Adele every second. Her album will go to No 1 on iTunes on pre-sales alone.

But that’s to come. In the lounge at XL, When We Were Young finishes playing for a second time, and we sit in silence for a moment, giving the song some room. Then Adele opens her eyes and says: “I feel like I’ve just done a school play, and nobody’s clapped yet.”

It’s beautiful, I say.

She beams. Bending at the waist, Adele performs an exaggerated, pantomime bow. She flaps her fingers at her reddening cheeks, blinks rapidly, and says: “Well, fucking phew.”

0 comments:

Post a Comment